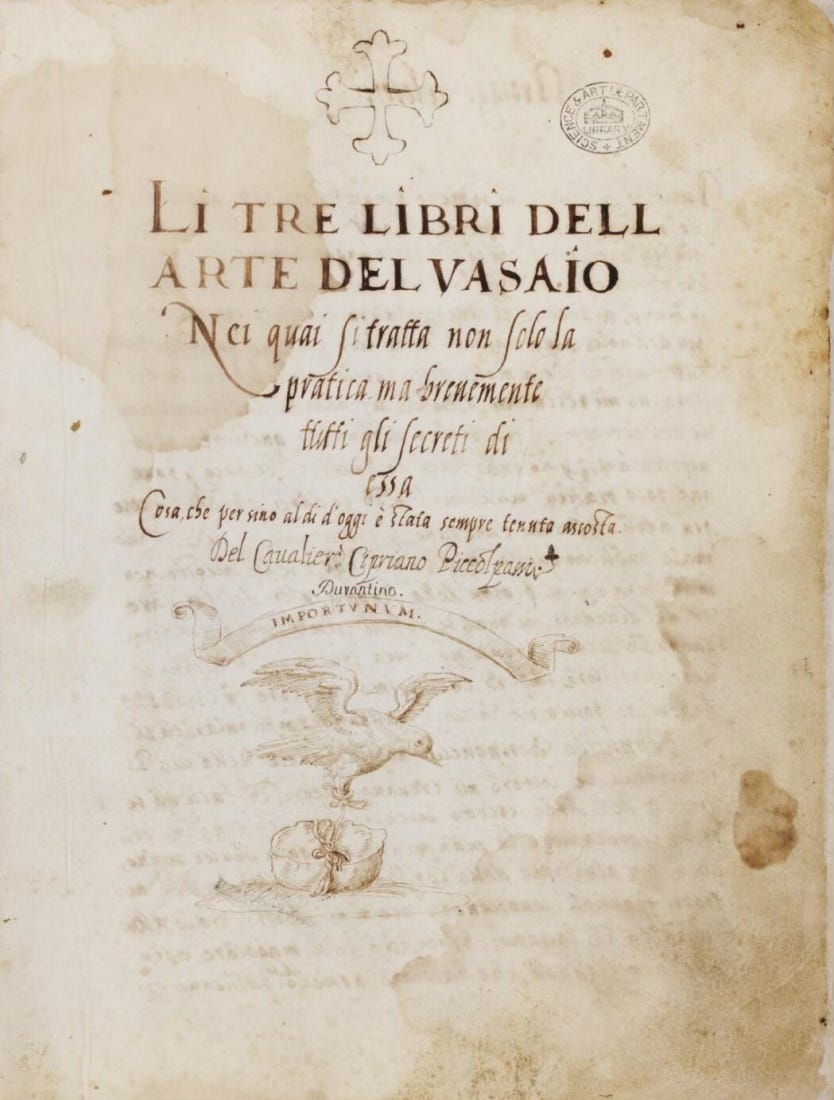

Italian Renaissance Maiolica, tin glazes and Piccolpasso’s "The three books of the potter's art"

In which I discover how the fancy set of plates I grew up with is connected to Renaissance maiolica.

Welcome back! This article has been a couple of months in the making and I hope you enjoy it. The amount of tangents and interesting areas of research that have emerged from working on what I initially thought was going to be a simple article about an old manuscript, have not failed to surprise me. May the gods save the Berlin Staatsbibliothek, as they seem to have all books I have ever desired as well as access to Jstor. If you enjoy thoroughly and obsessively researched articles about the history of ceramics and the many connections to contemporary culture, consider becoming a paid supporter. You will have access to an additional monthly post, as well as a few previously published recipes. In 2025, I am also planning on publishing a series of interviews. Do you have knowledge about some obscure and/or interesting part of ceramics history? Get in touch!

In 1860, John Charles Robinson was on a business trip to Florence, rummaging through heaps of antique papers, trinkets and pots. This was one of many “hunting” expeditions for the artist and curator, although he did have a special appreciation for Italy, as he had written in a letter home in 1851:

It is curious enough but I seem to have seen this before; and I can scarcely divest myself of the notion that I once lived here centuries ago. I feel as if I had got home at last.1

It was in Florence in the winter of 1860, while Italy was in a tumultuous time of Risorgimento that will end up with the unification of the country a year later, that he found an old manuscript and acquired it for just under 46 pounds.2

Robinson was not a random artist, rather the curator of the South Kensington Museum, now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A Museum) in London, and the old manuscript he acquired was Cipriano Piccolpasso’s 'Li tre libri dell'arte del vasaio' (The three books of the potter's art), a 16th century one-of-a-kind treatise about the production of Maiolica in Renaissance Italy.

Robinson purchased the manuscript from Giuseppe Raffaelli, the author of another book on Italian Renaissance Maiolica, published in 1846: “Memorie istoriche delle maioliche lavorate in Castel Durante o sia Urbania” (Historical memories of the maiolica ceramics made in Castel Durante or Urbania). It was particularly ironic that Robinson purchased Piccolpasso’s manuscript from Raffaelli, since the latter was an outspoken critic of those who let national artefacts leave the country, as he explained in his book’s introduction3. His words exude patriotic pride and melodramatic hurt4 at the thought of great Italian masterpieces enriching the walls of foreign museums, in what he calls an “indelible contempt”5. It is possible, as some have argued, that Raffaelli did not quite appreciate the manuscript for what it was or that he didn’t consider it as valuable once it had been published.6

Cipriano Piccolpasso’s 'Li tre libri dell'arte del vasaio' is now in the permanent collection of the V&A Museum and accessible to all who want to see it, even online.

Italian Renaissance Maiolica

Piccolpasso’s manuscript deals with the production of maiolica in 16th century Italy and it is considered the first illustrated European manuscript about ceramics.7

In Italy, Maiolica is a term used to describe tin-glazed decorated pottery: low-fire pottery that is covered with an opaque tin-white glaze and then painted. The decorations range from simple to ornate. Having grown up in Italy and travelled the country extensively, I have mostly heard the term used in conjunction with a certain callback to traditional wares. Italian maiolica tradition is far from monolithic - something that Piccolpasso also explained in this book - with many regional centres having developed their own unique style.

In English, maiolica is often used to describe Renaissance wares from Italy.8 Piccolpasso’s book - as we will see below - used the term to describe tin-glazed decorated pottery that also included the use of lustre.9 .

There would be no maiolica without tin glazes.

Tin is an important material in the production of glazes as, thanks to its refractive properties, it acts as a very effective opacifier, along with zircon.

There is some debate as to when tin glazes were first discovered and used. Generally, it is believed that the Babylonians discovered the opacifying properties of tin and used it in the production of tiles.10 On the other hand, a spectroscopic examination of white Babylonian glazes conducted by the British Museum Research Laboratory seems to indicate that there was no tin in these glazes.11

If there is debate as to whether tin was in use by the Assyrians, there is more proof that tin glazes were (re)discovered in Mesopotamia (in an area corresponding to current Iraq), from around the 9th century AD. Here too, however, there are debates as to the context in which tin was used, specifically as the generally accepted theory is that Islamic potters were attempting to imitate whitewares imported from China.12 A 1997 paper by R.B Mason and M.S. Tite argues that the use of tin as an opacifier was part of the technological developments in glaze making that had started much earlier and were driven by local demand.13 In a more recent study based on surface analysis of pots, the authors argue that the use of lead in the production of yellow opaque glazes provided for the context in which white tin-based glazes developed, rather than it being a response to imported Chinese whitewares.14

The other important development that made maiolica possible was the invention of lustre, which also took place in Iraq. Lustrewares were achieved by applying a suspension of copper and silver or gold on glazed pieces, which were then refired in a reduction atmosphere. The technique was expensive as it required an additional firing and results were not guaranteed.

These two techniques made their way to North Africa and Spain and eventually to Italy, around 1200 AD.15

The origin of the word maiolica is interesting because it is probably the result of a misunderstanding. It is believed that once the wares arrived in Florence, people started calling them maiolica after the island of Maiorca, although this is not where the pottery came from. Spanish lustreware were called “obra de malica” (Malaga ware) and it seems that the term malica, misunderstood to mean “Maiorca” was transformed into maiolica and the word stuck.16

Once these tin-glazed pieces arrived in Italy through Sicily, they were all the rage. Local production initially involved reproduction but soon, once the tin glazes and lustre technologies were mastered, imitation gave way to a proliferation of unique styles.17 Tax rolls from North and Central Italy show an increasing number of potteries, with local princes competing against each other to attract talent and start up local pottery production.18

The emergence of maiolica played an important factor in the development of a luxury market in Italy during the Renaissance19. In a fascinating article about the economic and social world of Italian Renaissance maiolica, Goldthwaite traces the growing demand for maiolica to the general increase in wealth after the Black Death of 1348 decimated the population, along with a growing class of skilled workers who could demand higher wages.20 The question as to why people chose to spend their money on maiolica was more complicated and, according to Goldthwaite, it could be linked the transformation of eating habits in Italy. Suddenly, more pieces were required on the table as people were not merely eating from a shared bowl anymore: they were each assigned their own plates. The variety of foods available also increased, so Italians were eating more elaborate meals. This coincided with the codification of dining etiquette, which involved the order of courses and types of plates that were to be used with specific foods. This is the time when the terms “credenza” and “servizio” entered into use.21

A servizio is a set of fancy plates, bowls and serving vessels that are to be used on special occasions and are often passed on to the next generation. My servizio, the collection of precious plates and bowls I grew up with, consisted of a set of off-white decorated plates featuring delicate lustered branches and birds. Very much like in the Renaissance22, this collection was stored in a credenza, a tall wooden display cabinet with glass doors and drawers. The plates were only used, not before being properly cleaned, during our traditional Christmas and Easter family celebrations.

Eventually, Italian maiolica was exported throughout Europe, with interested parties attempting to start up their own centres of production. This may also explain why Piccolpasso’s book came to be.

Cipriano Piccolpasso’s 'Li tre libri dell'arte del vasaio': context and audience

Cipriano Piccolpasso (1523-1579) was not a professional potter himself. He has been described as a doctor, a lawyer, a lover of the arts and a nobleman. He did however create one of the most important pieces of writing on ceramics ever produced.

A considerable amount of writing has been published on this document so I am not attempting to present a comprehensive overview of his work. I am, however, interested in a couple of aspects surrounding this manuscript.

The first has to do with the context of its creation.

Piccolpasso is said to have been approached by cardinal François de Tournon, ambassador for the French King to Italy, about writing an overview of Italian maiolica production, presumably because of French interest in establishing their own national industry. The manuscript was not published until 1857 and it is unclear whether the text as it stood was written with the idea of being given to someone with the standing of the French cardinal. According to Rowan Watson, who wrote the introduction to the 2007 annotated Italian publication of the book (and the version I have read), the manuscript looked like an author’s copy, with beautiful calligraphy but not particularly elegant and certainly not the kind of text that would be given to the representative of a French monarch.23

The second aspect pertains to the intended audience of the manuscript.

When reading the book it is evident that Piccolpasso’s audience was the sophisticated crowd who wanted to know about the arts. The goal was to inform art connoisseurs about the way these pieces were made so that they could better appreciate them.24 For this, he visited many workshops and observed potters at work.

Even though the books are considered to be providing an accurate representation of the techniques used in the production of maiolica in Renaissance Italy, Piccolpasso himself was aware that potters kept their secrets. In the prologue to the book, Piccolpasso preemptively addressed his detractors, putting together a rebuttal to the main critiques that may be aimed at the manuscript (a 16th century version of “don’t @ me”). To those who may complain about his “simple” language and crude drawings, he said that he was writing in his own local parlance and did his best. (I am surprised he didn’t mention the fact that he was a trained painter himself). To those who criticised the fact that he was revealing the long-kept secrets of master potters, he responded that he wanted to disseminate knowledge of the art form and that “it is better that many know what is good rather than a few keep it hidden”25. To those who accused him of writing about an art form he did not understand or practice (Piccolpasso mentioned in passing that he was an amateur potter) or that he should have dedicated himself to more useful endeavours, he said that while he did not invent the art form, he did it justice and that “he could not imagine to talk about more useful things that those that are useful to others”26.

“We need to be careful about the moon”

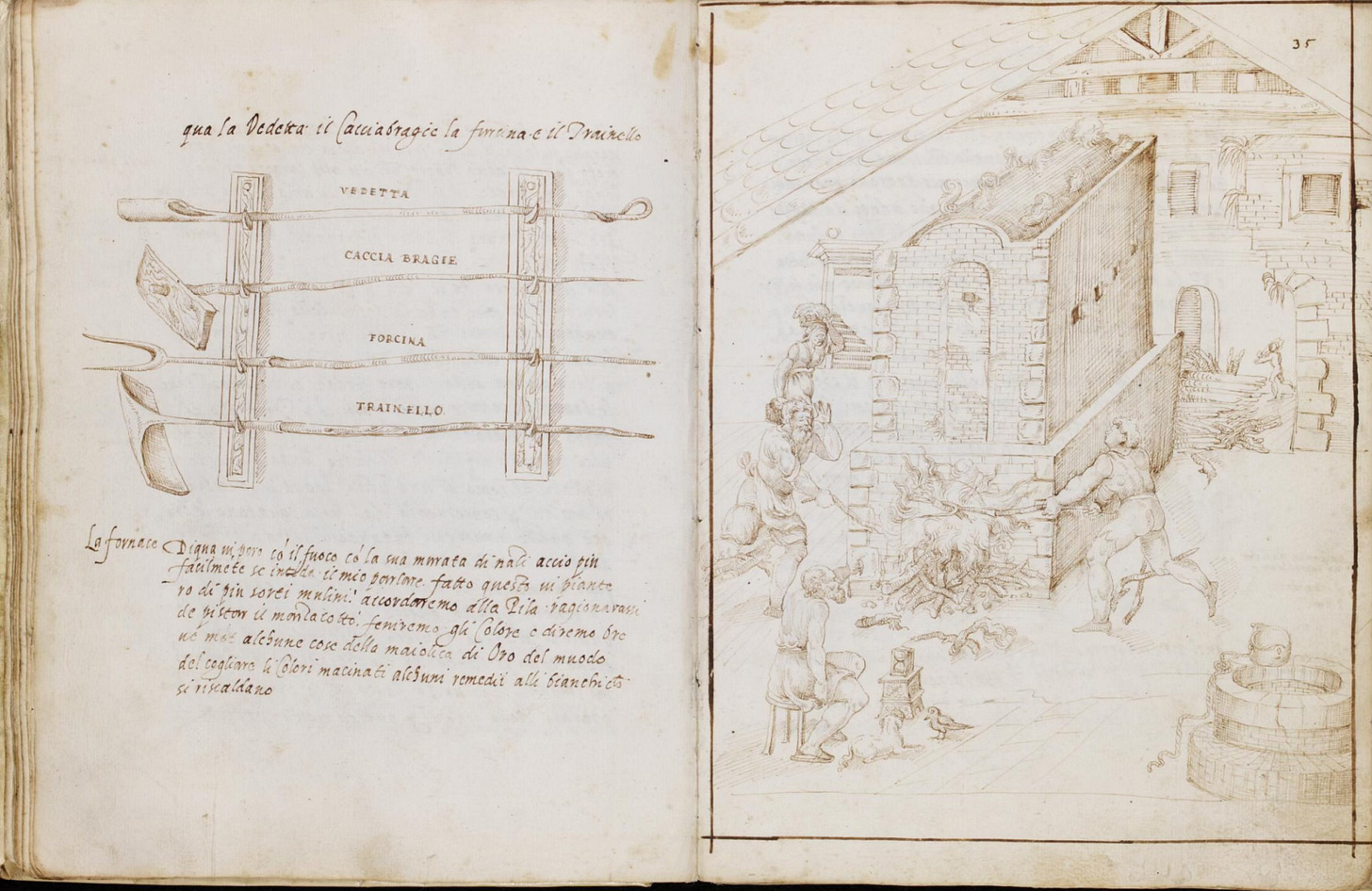

The 70-page manuscript is divided into three books. The first book deals with the collection and preparation of clay, the making of pottery wheels, the turning of various shapes on the wheel and the refinement of work.

The second book deals with the creation of various glazes, overglazes and lustre, with references to the specific techniques used in certain cities. The third book addresses the production of brushes and painting techniques.

Virtually every sentence of this book has been analysed and put into context and compared with other historical texts. The breadth of analysis also shows the continuing relevance of this text, particularly as the drawings of tools, kilns and techniques can elucidate and serve as a comparison point against tools used at different times for the production of pottery. The section dealing with fire chasers and other kiln-related tools, for instance, has helped to further the understanding of the use of similar tools depicted in scenes painted on Athenian vases, centuries before Piccolpasso’s manuscript27.

Below I have chosen to highlight two areas of the third book that I thought could be interesting.

Modo di dipingere: how to draw

This section appears at the beginning of the third book and explains how colour is painted on pieces after the glaze had been applied. The translation from the original Italian is mine.

Painting vases is different from painting on canvas because painters usually can stand, while those who decorate vases are always sitting, otherwise they would not be able to check how the drawing will look. The object to be painted must be kept on the knees with a hand underneath. This is valid for flat objects, while closed forms are painted with the left hand inside…. Some closed forms are painted while they rest on the left knee….

It is important to be careful with not putting brushes that have been used with a color in another one, as they don’t all tolerate this well. For instance, one should always use the same brush for white. If one wants to use a brush that has been previously used to paint with a different color, the brush must be perfectly clean or the color will be stained. The same applies for other colors except for green, in which one can put a brush that has been used for yellow. The opposite is not true: if you put green in yellow, it will become green. However, if you have a brush that was used to paint light yellow with, you can put this brush in the green as it will also help the green look better if it starts to go bad28.

Finally, when it comes to firing, Piccolpasso talks about the rituals of the kiln29.

...we need to be careful about the moon, because this is very important. I have heard from those who are experienced that if you start the firing on a new moon, the fire will lack shine, just like the moon does not have its shine. [...]30.

Conclusion

We may not be sure why Piccolpasso wrote a manuscript about the craft of maiolica, but this work has been invaluable in helping us understand the mastery involved in creating the beautiful 16th century works of art. Part of my personal fascination for this manuscript rests in the fact that this is the only extensive piece of writing on the subject from that time and that I can read it in its original language. I can imagine potters opening the doors of their workshops to him, allowing him to observe them at work. I wonder if these potters knew the purpose of the manuscript. Did Piccolpasso tell them it was going to be published or that it was going to be handed over to a French cardinal, who may use it to build up their international competition? Given the high estimation in which Italian maiolica was held at the time (and still is to this day), it is possible that Piccolpasso appreciated the opportunity of showing off the pride of Italian craftsmanship to a French dignitary.

Anthony Burton, Vision & Accident: the story of the Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A Publications, 1999, p.62

Cipriano Piccolpasso, Li Tre Libri Dell’Arte del Vasaio, in Facsimile e versione in italiano moderno, Éditions La Revue de la Céramique et du Verre, 2007, p.7

ibid

In case my choice of words has not made it clear enough, I am being sarcastic.

Giuseppe Raffaelli, Memorie istoriche delle maioliche lavorate in Castel Durante o sia Urbania, 1846, p.7

Piccolpasso, p.7

Timothy Wilson, “Making Maiolica”, Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2013, Vol. 87, No. 1/4, Italian Renaissance and Later Ceramics (2013), p.6

Ibid

Timothy Wilson, “The Impact of Hispano-Moresque Imports in Fifteenth-century Florence”, Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2013, Vol. 87, No. 1/4, Italian Renaissance and Later Ceramics (2013), p.10

Emmanuel Cooper, 10,000 Years of Pottery, The British Museum Press, 2005, p.86

J. E. Dayton, “The Problem of Tin in the Ancient World”, World Archaeology, Vol. 3, No. 1, Technological Innovations (Jun., 1971), p. 49

Emmanuel Cooper, p.86

R.B. Mason and M.S. Tite, “The beginnings of tin-opacification of pottery glazes”, Archaeometry 39, 1 (1997), p.57

Michael Tite, Oliver Watson, Trinitat Pradell, Moujan Matina, Gloria Molina, Kelly Domoney, Anne Bouquillone, “Revisiting the beginnings of tin-opaci ed Islamic glazes”, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 57, May 2015, Pages 80-91

Timothy Wilson, “Making Maiolica”, p.6

Timothy Wilson, “The Impact of Hispano-Moresque Imports in Fifteenth-century Florence”, p.10

Richard A. Goldthwaite, “The Economic and Social World of Italian Renaissance Maiolica”, Renaissance Quarterly, Spring, 1989, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring, 1989), p.5

ibid

ibid

ibid, p.18

ibid, p.21

See Patricia Simons, “The Cultural Context of Maiolica in Renaissance Italy”, Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2013, Vol. 87, No. 1/4, Italian Renaissance and Later Ceramics (2013), p.15

Piccolpasso, p.7

ibid

ibid, p.15

ibid

See John K. Papadopoulos, Ceramicus Redivivus: The Early Iron Age Potters’ Field in the Area of the Classical Athenian Agora, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2003, pp.9-15

Piccolpasso, p.48

For another article about kiln rituals and kiln gods, have a look at my article, “Who are the kiln gods anyway”.

ibid, p.52