Passing down the craft: the oldest recorded glaze recipe

Babylonian Clay Tablets, the Ishtar gate and the library of Ashurbanipal

Hi there, before we delve into this post about ancient texts and alchemy, I wanted to say thank you for being here! This is where I usually ask you to support my little publication by becoming a paid subscriber. If you know a potter or history nerd, there are also options to gift a subscription. Other ways to support me include liking, commenting and sharing this post. Thank you so much!

Between November and May 2020, the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in New York hosted an exhibition named “A Wonder to Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon's Ishtar Gate”. The exhibition explored ideas of creation, craft and materials through a number of artefacts, including remains of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate. The famous Ishtar Gate, built in the 6th century BC by order of king Nebuchadnezzar II, is a wonder to behold indeed. The gate features stunning glazed clay tiles depicting animals in reliefs.

A part of the gate was reconstructed (featuring a number of original and modern bricks) in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The Museum is currently closed for renovations, but we can enjoy a virtual tour on the Museum’s website. The Gate, we learn from the virtual guide, was constructed in phases: the first phase consisted of unglazed animal reliefs, the second phase which built on top of the first, featured coloured glazes but no reliefs, while the third and final layer combined coloured glazes and reliefs. The Ishtar gate was built in honor of Ishtar, the goddess of war, fertility and love. She is symbolised by the lion, which features heavily on the building.

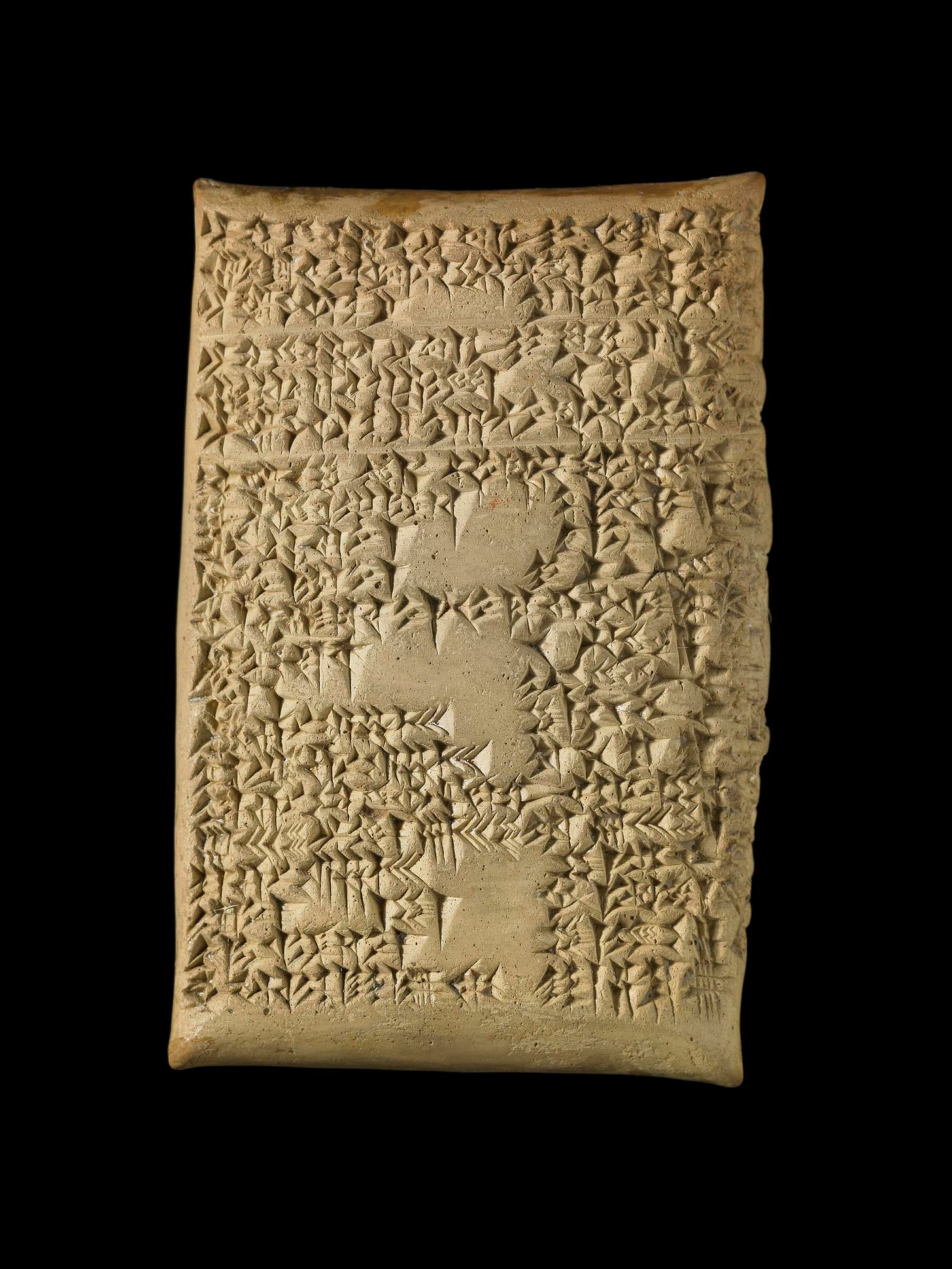

Among the artefacts on show at the exhibit in New York, there were a number of cuneiform clay tablets on loan from the British Museum. One of them also happens to be the oldest recorded glaze recipe.

The oldest among them, shown above, measures around 5 by 8 cm and is said to be from Tell Umar (current Iraq). The tablet is intact and inscribed with lines of cuneiform script. The date of origin spans from 1400 to 1200BC, centuries before the glazed tiles that make up the Ishtar gate were created.

The person who wrote on the tablet seemed to have chosen a form of cryptography to conceal the secrets of the craft, so that only craftspeople in the same Guild would have been able to decipher it1. Gadd and Thompson went through the process of transcribing and translating the text, which I will reproduce below2.

The tablet contains ingredients and instructions to make two glazes, which are to be combined, as well as the description of rituals that are to precede the application of the glaze. The making of glass was both science and alchemy, with the ultimate success not being certain and depending on a number of rituals.

The first recipe was for a green copper glaze which contained:

60 parts zukû -glass

10 parts lead

15 parts copper

half part saltpetre

half part lime

What is zukû glass? There is quite a lot of literature on the subject. According to Brills, this is an intermediate product - a glaze in itself - which is achieved by mixing quartzite pebbles with the ashes of the naga plant3.

The first recipe is mixed and fired.

A second recipe, for “Akkadian copper”, is then provided:

60 parts zukû-glass

10 parts lead (presumably)

14 parts copper

2 parts lime

1 part saltpetre

This mixture is also to be fired in the kiln and the two glazes are then to be combined in equal parts.

The recipe also describes the making of a green clay body by “steeping the clay for three days in a mixture of vinegar and copper”. Once the clay is workable, a pot can be produced from it.

Before the glaze is applied, however, the inscription mentions the need to perform a ritual. It is unclear what exactly is needed for the ritual: the text mentions "incomplete dead”, which the authors have interpreted to mean embryos, even though it is not specified. The remains were sprinkled with spices and once the ritual was complete, the pot could be glazed.

“On the face of thy bast (representing the pot ready to receive the glaze( ?)) thou shalt put the glaze (lit. 'stone'), dipping it and taking it out (of the liquid glaze); thou shalt bake it (and) cool (it).”4 The pot was then to be fired a second time and a third time, after receiving additional materials.

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal

Centuries later, in the 7th century BC, a monumental library was being built in northern Mesopotamia: the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal. The library will go on to contain over 30,000 clay tablets, including the Epic of Gilgamesh. Room 55 of the British Museum features a selection of these tablets.

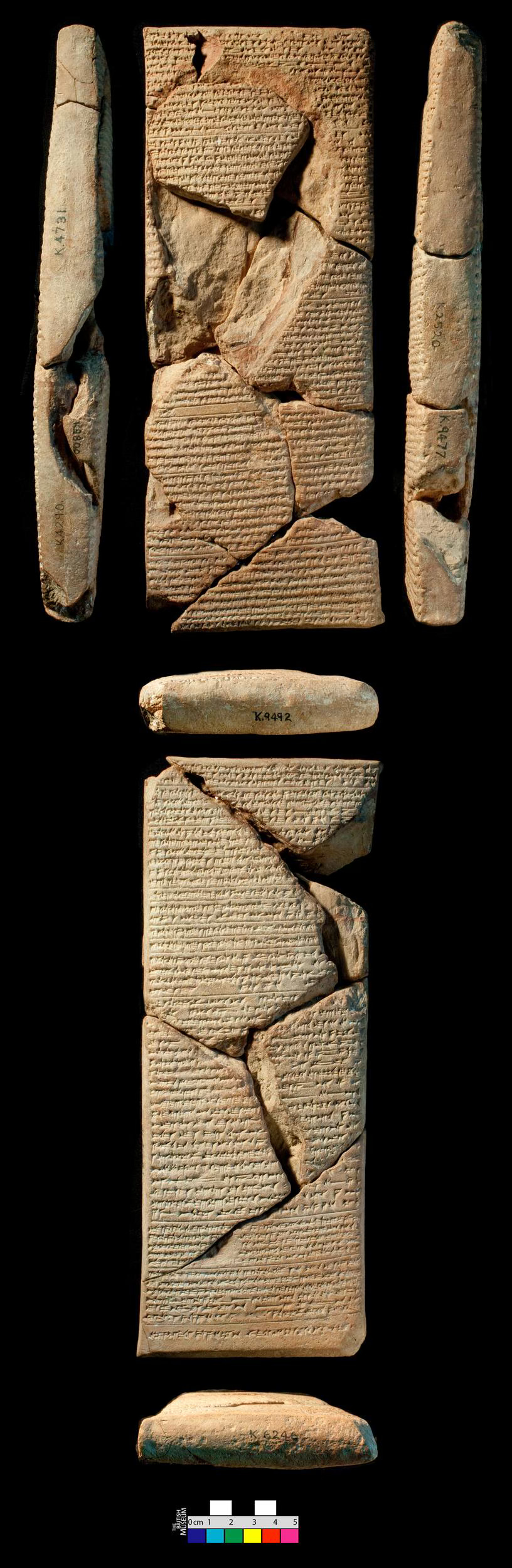

Among the clay tablets found in the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, we find fragments of glass recipes (depicted below).

The recipes were first translated in German by Zimmern in 1925 and were then tested by Robert Brill who in 1972 presented his findings at the 5th Congress of the international association for the history of glass (5e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre), declaring that, indeed, these ingredients, when combined, made glass5.

Among these fragmentary tablets we find instructions for the building of a kiln:

“When you lay the foundations of a glass-making kiln, [you search repeatedly for a suitable day] during a favorable month, so that [you may lay] the foundations of the kiln. As soon as [you complete (the construction of)]the kiln, in the house of the kiln (...) you set down Kūbudemons in order that an outsider or stranger cannot enter; one who is impure cannot cross their (Kūbu demons’)presence. You will constantly scatter aromatics offerings in their presence.

On the day that you set down “glass” (lit: "stone") within the kiln, you make a sheep sacrifice in the presence of the Kūbu demons, (and) you set down a censer (with) juniper, you pour honey (over it). You (then) ignite a fire at the base of the kiln. You (may now) set down the “glass” within thekiln. The persons that you bring close to the kiln (...) must be purified, (only then) can [you allow them to sit near](and overlook) the kiln.

You burn various wooden logs at the base of the kiln(including): thick logs of poplar that are stripped, and quru-wood containing no knots, bound up with apu-straps; (these logs are to be) cut during the month of Abu; these are the various logs that should go beneath your kiln.” 6

Beyond recipes

While a lot of literature has been devoted to the analysis of these tablets, we are not quite sure of their meaning or intended audience7.

A number of scholars have argued that these texts are better understood within Assyrian’s scribal traditions8. The idea of writing down technology or procedures was, at that time, seen as a process with which lost knowledge was to be recovered9, which also explains some of the vague technical terms that we see on some of the tablets, or why specific measurements are lacking from the instructions on how to build a kiln10. The argument is that the scribes were more concerned with “maintaining the literary tradition”11, rather than with the production of technical instructions12. (One of the purposes of the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal was, after all, to assemble all known knowledge).

These recipes are then less about the know-how - detailed instructions to be followed - and more of an attempt to document “found” knowledge.

Even with all of these open questions, these texts are incredibly fascinating for us potters of the present. The presence of rituals is an integral part of the tradition, and while these rituals might have changed, we understand that our craft is not devoid of disappointments and surprises.

What do you take away from these ancient texts?

A Middle-Babylonian Chemical Text, C. J. Gadd and R. Campbell Thompson, Iraq, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1936), p.87

Please do not try to reproduce this recipe in your studio, assuming you would even be able to find the ingredients.

Brill, R. H. "Some Chemical Observations on the Cuneiform Glassmaking Texts." Annales du 5e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre. Liège: Edition du Secrétariat Général, 1972, p.332

C. J. Gadd and R. Campbell Thompson

ibid

Translation: https://oracc.museum.upenn.edu//glass/P393786

See, among others, J. D. Muhly, “Reviewed Work(s): Glass and Glassmaking in Ancient Mesopotamia by A. Leo Oppenheim, Robert H. Brill, Dan Barag and Axel Von Saldern” , Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 1972, Vol. 24, No. 4 (1972), pp. 178-182

Eduardo A. Escobar, “Glassmaking as a scribal craft”, in A Wonder to Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate. Catalogue of the exhibition. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University.

Ibid, p.122

Ibid, p.121

J. D. Muhly, citing Oppenheim ib, p.180

ibid