The Ceramics of the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy: the functional ceramics of Hobbits

A look at the ceramics made for the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy in a broader context

This post may be too long for your email provider: to read it in its entirety, switch to the browser (there should be a link at the very top) or the app.

This article is the first in a small series in which we will examine the ceramics that feature in the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy. We will look at Tolkien’s inspiration, his words, his view of crafts, medieval ceramics, director Peter Jackson’s approach to making the movie and the behind the scenes props.

If you love the Lord of the Rings, these posts will entertain you and bring you back into that world. But if you do not care for Tolkien’s masterpieces, you will still hopefully enjoy my attempt at understanding how the artist behind the ceramics used on the set of the Lord of Rings arrived at those designs. Literature on this is sparse so I used primary sources: I re-read passages from the Lord of the Rings books (and the Hobbit and the Silmarillion), watched the movies and the behind the scenes footage and then came to my own conclusions. I had 30 pages of notes and I do not know how I managed to edit it down, so for that alone I deserve a treat.

To that end, there is a way to support me through a paid subscription. I enjoy researching and writing about ceramics and I would love to be able to spend more time doing it. Your support will allow me to do just that.

You can also gift a subscription to a friend who loves ceramics.

This week we will focus on the world of the Hobbits and we will look at the ceramics that were produced for the set of the movies and attempt to place them in the context of the story and Tolkien’s background.

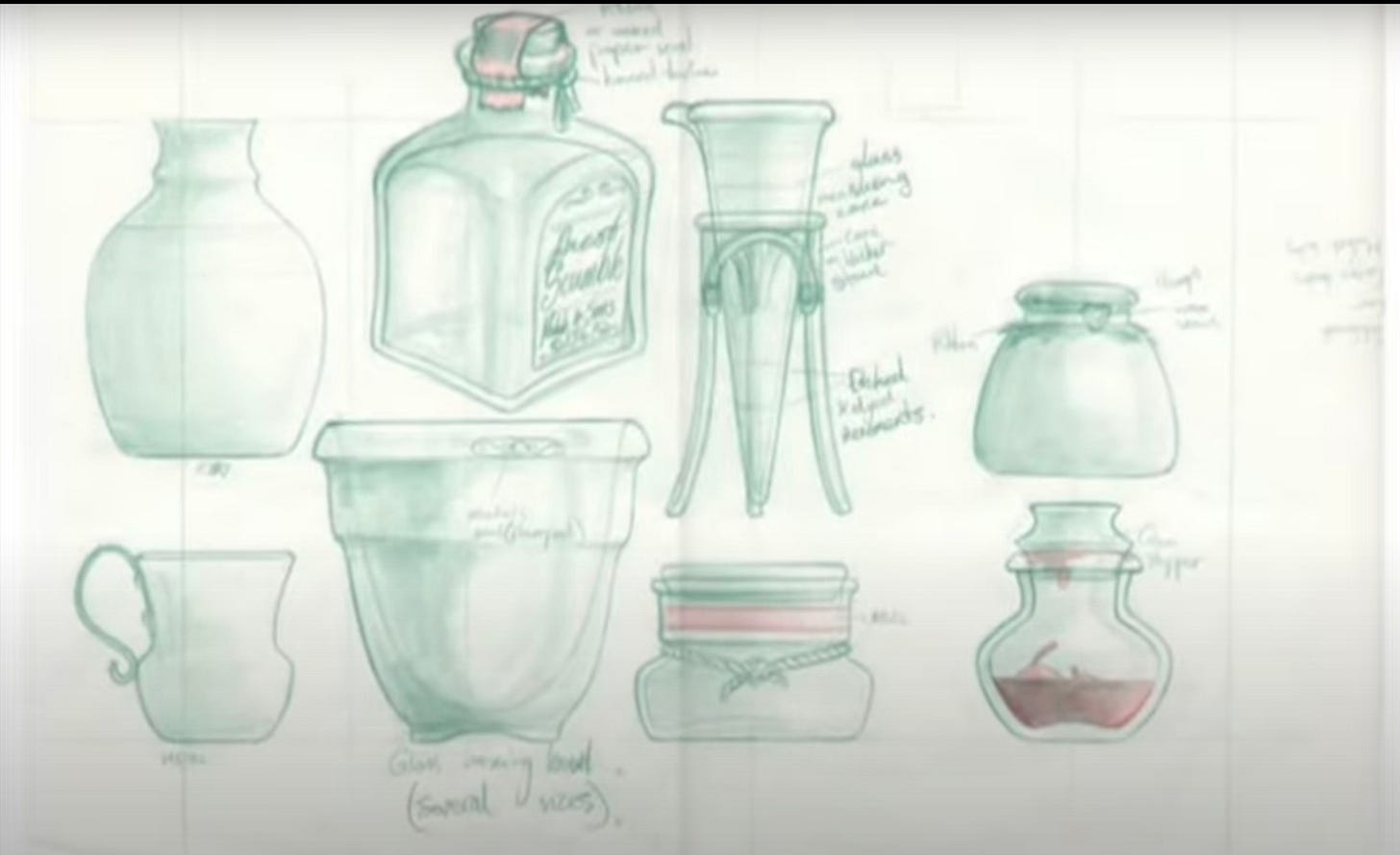

This post is a type of reverse engineering: as a ceramic artist, I am attempting to go through a similar process to what the potter who made most of the ceramics for the movie, Mirek Smisek, would have gone through before making his work for the set.

In abstract, this is also an example of how we may go about translating inspiration and facts into a ceramic collection. To that end, I will look at the way Tolkien describes Hobbits, and what we can infer from the text about their approach to crafts.

Tolkien’s approach to arts and crafts in his world-building

J.R.R. Tolkien’s work can only be described as monumental. I will not attempt to cover or introduce his work because this would be widely outside of the scope of this post and I would not be able to do it justice. I will have to concentrate on specific aspects of his work that pertain to my objective here, but of course, there is so much more to say.

Tolkien had been working on his legendarium1 well before the Hobbit was published in 1937. The ideas guiding his world-building were deeply rooted in his love for languages and his studies in philology. Even if you know very little about Tolkien’s work, you will probably know that he invented languages for many of the peoples he described and his universe is incredibly detailed.

In attempting to coherently write about Tolkien’s approach to arts and crafts, I looked at his drawings and artworks, some of his letters and the impact of the Arts and Crafts movement in his art.

While Tolkien’s stories covered much grander themes, crafts, understood as the creation of objects, are quite an important part of Tolkien’s wider legendarium, from Fëanor’s Silmarilli, to the Rings of Power, to the weapons and artefacts and jewellery created by the Elves and the impressive architecture and metalsmithing of the Dwarves. Craftsmanship is heavily featured in Tolkien’s world, both as a display of skill and artistry, and as an attempt, by some less than pure characters, to control and model the world to their liking.

Tolkien employed the term “sub-creation” to describe the creations of beings who were themselves the result of the creation of Eru Ilúvatar, the One, who created Arda (the Earth)2. While sub-creations could be honourable, there is also the potential for the Fall, which occurs when a creator becomes possessive “clinging to the things made as its own”3. This is what happened to Fëanor, a great Elf and metalsmith, who was obsessed with the Silmarilli, the gems he created, something that would eventually cause his downfall4. A very similar thing can be said about Sauron, who, in his aim to possess and control the beings of Middle Earth, made the Rings of Power and imbued them with his malice.

We find, in Tolkien’s writings and descriptions of the sub-creations of the beings of Middle Earth, an appreciation for the handicrafts, much like William Morris and his group. While we do not have the space here to fully analyse the Arts and Crafts movement, Tolkien was clearly influenced by it in his drawings (see below for an example)5. The Arts and Crafts movement highlighted the importance of beautiful objects made by hand, in a repudiation of industrialisation. Tolkien was known to love the countryside (the Hobbits are the most obvious expression of the return to nature - see below) and not being incredibly fond of industrialisation and modernisation in general.

The Hobbits

Hobbits are a simple folk. They are between 2 and 4 feet tall (60cm to 1,2m) and Tolkien describes them as “unobtrusive but very ancient people [who]..do not or did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom, though they were skillful with tools”6.

Tolkien continues:

“They dressed in bright colours, being notably fond of yellow and green; but they seldom wore shoes, since their feet had tough leathery soles and were clad in a thick curling hair, much like the hair of their heads, which was commonly brown. Thus, the only craft little practised among them was shoe-making; but they had long and skilful fingers and could make many other useful and comely things. Their faces were as a rule good-natured rather than beautiful, broad, bright-eyed, red-cheeked, with mouths apt to laughter, and to eating and drinking. And laugh they did, and eat, and drink, often and heartily, being fond of simple jests at all times, and of six meals a day (when they could get them). They were hospitable and delighted in parties, and in presents, which they gave away freely and eagerly accepted.”7

Hobbits loved gifts so much that they had whole structures dedicated to them:

“The Mathom-house it was called; for anything that Hobbits had no immediate use for, but were unwilling to throw away, they called a mathom. Their dwellings were apt to become rather crowded with mathoms, and many of the presents that passed from hand to hand were of that sort.”8

So Hobbits were simple folk who lived in an idyllic place, the Shire, were fond of a simple life which included eating and drinking. They had an ancient history, appreciated beautiful things and learned a variety of crafts. Some of these crafts, they learned from others:

“The craft of building may have come from Elves or Men, but the Hobbits used it in their own fashion. They did not go in for towers. Their houses were usually long, low, and comfortable. The oldest kind were, indeed, no more than built imitations of smials, thatched with dry grass or straw, or roofed with turves, and having walls somewhat bulged. That stage, however, belonged to the early days of the Shire, and hobbit-building had long since been altered, improved by devices, learned from Dwarves, or discovered by themselves. A preference for round windows, and even round doors, was the chief remaining peculiarity of hobbit-architecture.”9

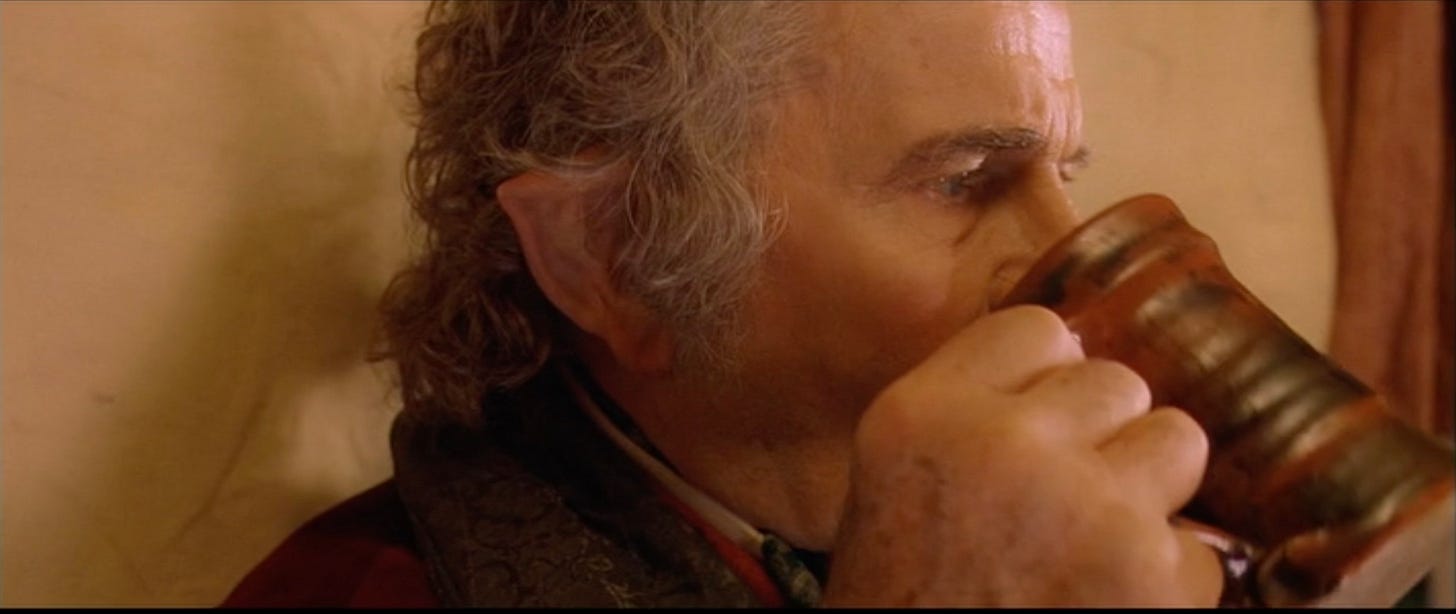

Bilbo and by extension Frodo, were “well-to-do”10 Hobbits. Bilbo had brought back many beautiful objects from his travels, which resulted in a funny situation when Bilbo left at the beginning of the “Fellowship of the Ring” and the other Hobbits were rushing to take possessions of his belongings. We can say that Bilbo was particular about his property. In The Hobbit’s An Unexpected Party, Bilbo is terrified that the Dwarves will destroy his precious plates, shouting to “please be careful!”11. While this does appear in the book, in Peter Jackson’s movie adaption, “The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey”, we hear Bilbo specify that this was “Westfarthing pottery!”12 . Unfortunately, we never really get to see this pottery up close. (In this post, deliberately chose to only focus on the props made for the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy).

While Tolkien tells us that Hobbits were skilled in crafts, we do not get a lot of detailed descriptions of their creations besides the structure of their dwellings. However, we can assume that they made pottery for functional use (and it seems that mugs were mostly for drinking ale) and that they probably used traditional techniques such as coiling or the pottery wheel. Considering that the Hobbits were numerous and lived in different areas and held big parties and get-togethers, it was more probable that the wheel would have been a more efficient way to produce large quantities of work. Since Hobbits were not fond of outsiders, they probably had little trade outside their borders and we can assume that they produced all of the pottery they used.

While the majority of the work would have simple lines and finishes, there would have been special pieces, passed on to generations and gifted for special occasions (as we learned: Hobbits were fond of gift-giving). These may be pieces with more elaborate decorations and used for special occasions. They probably fired their work in basic wood-burning kilns.

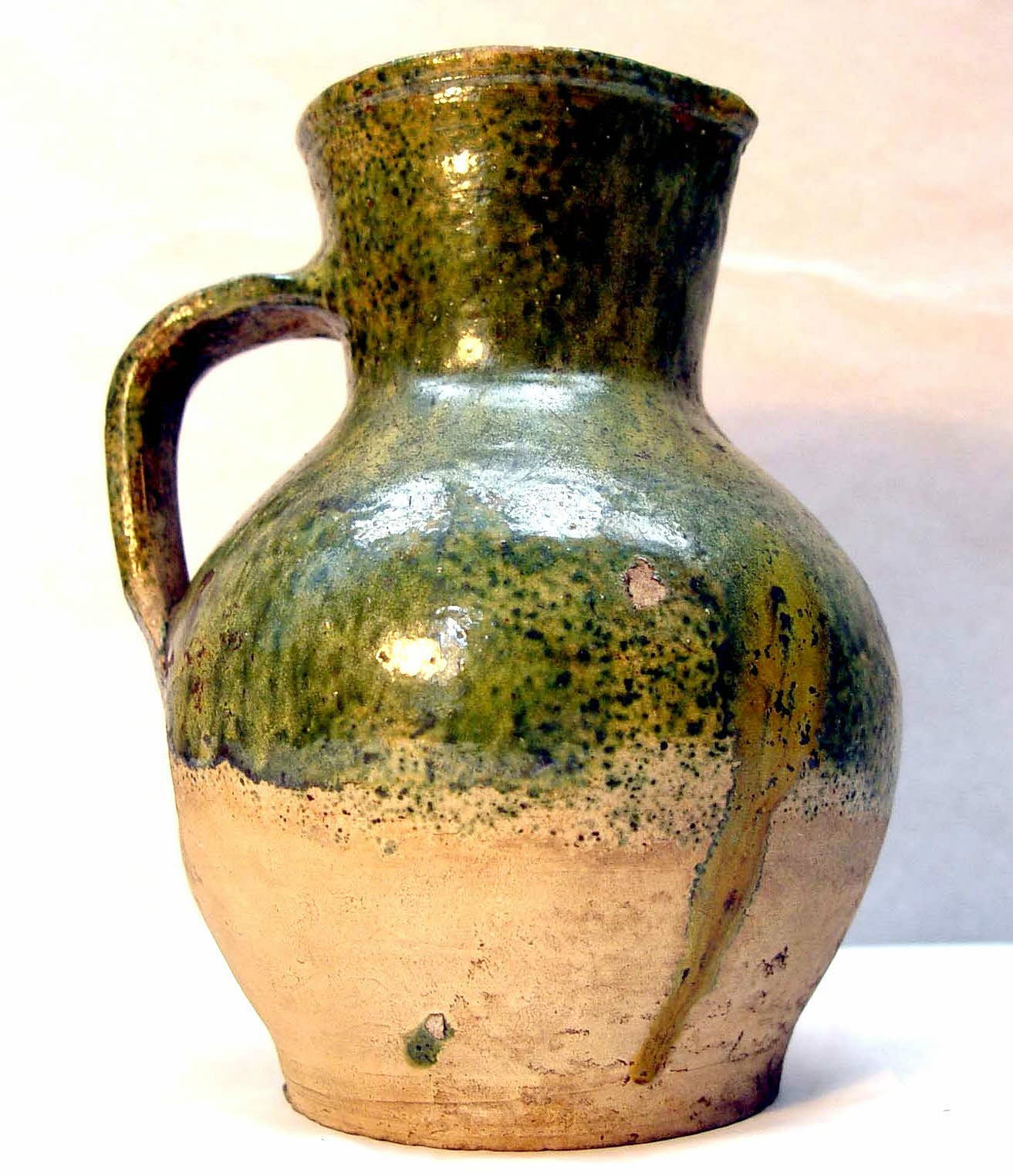

We have seen that Hobbits liked yellow and green and were very much in tune with nature, so we would expect earthy colours to feature heavily among those chosen for the pots.

From book to movie: the making of the Lord of the Rings

Peter Jackson and crew put incredible attention to every aspect of the movie. In the behind the scenes documentary to Fellowship of the Ring, Jackson recounts a speech he gave to the crew. He urged them to imagine that the events of the Lord of the Rings had actually happened, that they were ancient history and that they had the luck to actually be able to film in the original locations where those events took place.

When it came to making props and set design for the movies, Jackson and crew heavily relied on local craftspeople: metalsmiths, blacksmiths for weapons and armours, carpenters and, yes, potters.

The quantities of props that had to be made were impressive and many had to be made in duplicates of various sizes to account for the characters’ differing scales.

The design department worked with Alan Lee and John Howe, two renowned illustrators of Tolkien’s work.

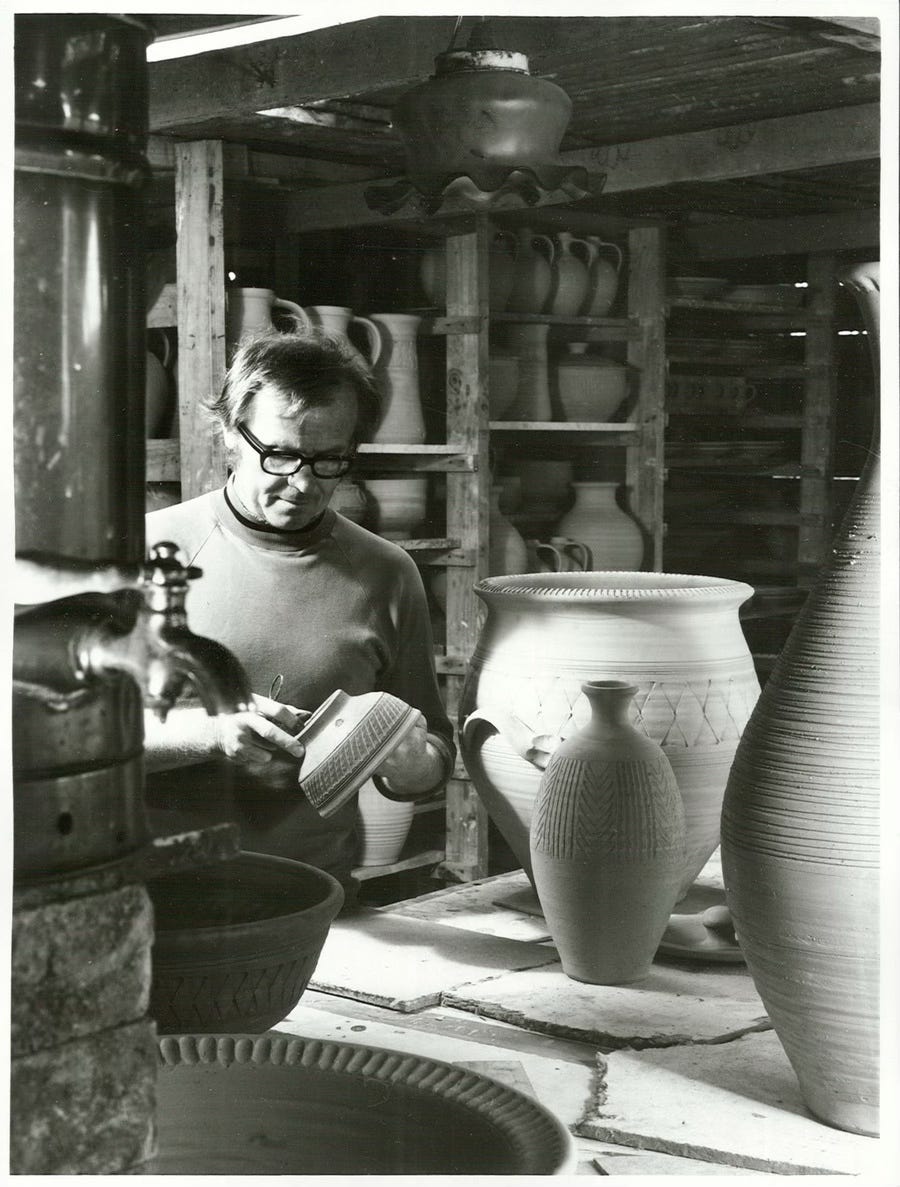

When it came to actually making the pottery for the sets of the movie, the task was assigned to Mirek Smisek, a potter born in Czechoslovakia in 1925 and who lived and worked in New Zealand until his death in 2013.

Smisek joined the anti-Nazi resistance during WWII, which resulted in his arrest and time in Nazi labor camps. In 1948, after the Communist Czech coup, he fled the country and settled in New Zealand.

In 1956, he became New Zealand’s first full time potter13.

In 1986 he was interviewed by the New Zealand Crafts Council Magazine and when asked whether he may ever get tired of his work, he responded with a quote that really warmed my heart: “Never, never, I love it. I believe in it. What else is more important? I have a desire to create beautiful things that will speak to other people and become part of their lives”14.

His work features beautiful gas fired stoneware jugs, bowls, plates, cups and some sculptural objects.

He fired his work in his famous beehive kilns, which were recently dismantled and moved to a different location with the purpose of creating a museum15.

There isn’t a lot of information about how he prepared for the work on Lord of the Rings. I could only find one article16 written by another potter who seemingly lifted the content from a now defunct place on the internet. Hence my whole point of doing the exercise of looking at the source materials.

In this article, Smisek said that he was greatly inspired by English medieval pottery, especially for the forms of the jugs. This isn’t surprising as the Lord of the Rings is indeed a medieval piece of literature.

English medieval pottery was not a monolith: styles varied greatly region by region17. In general, however, until the end of the 12th century, most pots produced were quite simple and made mostly for the household18. Lead- and copper-based glazes were also in use, as seen on the Tudor green jug below.

Looking at the pots produced for the movies and used by the Hobbits, we can clearly see the medieval influence. Most pots in the Shire are being used for drinking ale and are every-day pots. We see them at Bilbo’s party and at the tavern. They feature simple shapes and lines, no decoration and earth-toned glazes: mostly browns and greens with some celadons. Hobbits who were in charge of making ceramics would have probably dug up and processed local clay and relied on a limited selection of oxides for the glazes.

Smisek himself used local clay to his area in New Zealand and his glazes, which he formulated himself, contained red iron oxide, manganese and copper19. He made around 700 pots and the work took around 8 months to complete20.

We do see some beautiful barrel-shaped mugs and some pedestal cups that remind us of chalices21. Tolkien told us that Hobbits were skilled and these simple shapes have an elegance to them. I particularly love the tall mug in the foreground in the first photo below: the textured brown glaze, which appears to have gone through salt firing, beautifully contrasts with the interior white glaze. This mug is functional and simple, but simple things are often the hardest the get right.

When it comes to the pieces in Bilbo’s home, we see some pots that feature slip decorations and patterns, reminding us that Bilbo is indeed, well-to-do and the collected beautiful objects. The teapot and mugs have floral designs that are reminiscent of William Morris’ patterns. There also seems to be a credenza where decorated plates are being displayed. Might these be examples of Westfarthing pottery22? These were probably used on special occasions, and were important enough that they should be displayed when not in use.

Conclusion

Creating a collection of work is a lot like world-building. It can feel like a monumental task, full of questions. What are we saying with our work? What do we want people to feel when they see it? We communicate through many small decisions, from shapes to materials, from firing methods to decorations. This is what Mirek Smisek and everyone involved in the movie so skilfully executed with their work on the Lord of the Rings. They had to take all of what Tolkien said (or didn’t) about the Peoples of Middle Earth, and create objects that could take us further into the story, revealing information about traditions, quirks and history.

I hope that with this article I have manage to pay homage to some of that effort.

Before you come for me: I am using the term legendarium to broadly define any story connected to Middle Earth - I know some people disagree, but respectfully, chill.

See J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, edited by Christopher Tolkien.

Letter 131 to Milton Waldman (probably 1951), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded edition, edited by English edition by Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien, HarperCollins; Revised and Expanded edition (9 Nov. 2023), p.204

See J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, edited by Christopher Tolkien.

Wayne G Hammond and Christina Scull, J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator, Harper Collins (1998), p.10

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: the Fellowship of the Ring, Harper Collins (2007), p.1 (Prologue)

Ibid, p.2

Ibid, p.5

Ibid, p.6

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit, Harper Collins (2011), p.1

Ibid, p.13

The Westfarthing was one of the four sections (Farthings) of the Shire. The other three were North, South and East. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: the Fellowship of the Ring, p. 9

Strength and Freedom: Jenny Patrick and Neil Rowe write about Mirek Smisez, New Zealand’s first full time potter, New Zealand Crafts, Craft Councils Magazine 18, Spring 1986, Accessed September 25th 2024, https://repository.digitalnz.org/system/uploads/record/attachment/744/_mirek_smisek__strength_and_freedom___new_zealand_crafts_18__spring_1986.pdf

Ibid

Handle with care: Mirek Smišek pottery kilns on the move in Te Horo, the New Zealand Herald, 7th August 2020, Accessed September 25th 2024, https://www.nzherald.co.nz/kapiti-news/news/handle-with-care-mirek-smisek-pottery-kilns-on-the-move-in-te-horo/ZK6WAKQEKRFV5DJ2ECWGJVUQJE/

Lord Of the Rings Pottery, by Mirek Smisek, Pottery: Mashiko Potter, accessed Accessed September 25th 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20110207180411/https://potters.blogspot.com/2004/02/lord-of-rings-pottery-by-mirek-smisek.html

Paul Greenhalgh, Ceramic, Art and Civilisation, Bloomsbury Visual Arts (March 11, 2021), p.142

Ibid, p.144

Lord Of the Rings Pottery, by Mirek Smisek, Pottery: Mashiko Potter

Ibid

For an interesting catalogue of Medieval ceramics shapes, see Medieval Pottery Research Group, A Guide to the Classification of Medieval Ceramic Forms, Occasional Paper 1, 1998

In this article I did not look at the pottery made for the Hobbit movies, and that’s where the reference to Westfarthing pottery was made.